BLOG POST | 20 Oct 2022

Climate vulnerability demands conflict transformation approaches

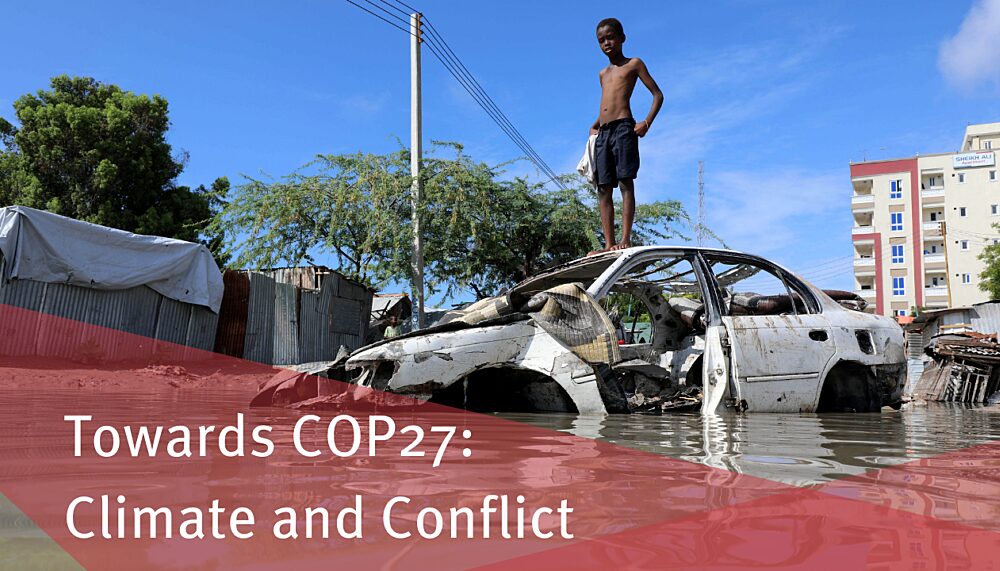

Towards COP27: Our article series on climate and conflict

At the upcoming COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, adaptation will be at the top of the agenda. To be effective, conflict transformation must be a part of that conversation.

By Tom Breese, Nike Löble

In many of the areas in which the Berghof Foundation works, climate change is deepening dividing lines, driving marginalisation, and making conflict even harder to resolve. Addressing the physical challenges is important – making crops more resilient and building flood defences, for instance – but overlooking the social dimensions of adaptation would miss a key opportunity to address the dangers posed by climate change.

In recent debates, the idea of climate change as a conflict driver has been eschewed in favour of its ‘risk multiplier’ effect. Yet, the risks identified are often social, such as weak governance, marginalisation and polarisation. Material risks, such as land degradation and crop failure play a far less decisive role than early proponents had thought.

In a recent study, Joshua Busby explores this phenomenon, asking why the same drought drove insecurity in Somalia and not in Ethiopia; and why successive cyclones caused much more destruction in Myanmar than in Bangladesh. The author finds that the different social and political realities in these cases are in large the culprits of their insecurity. Adaptation efforts should therefore focus on improving the social capital of affected communities, i.e. investing in relationships between individuals and networks built on reciprocity and trust.

Towards COP27: Our article series on climate and conflict

The Berghof Foundation is active in both facilitating dialogue and strengthening climate-focused mediation. In the lead up to COP27, we will be presenting our work in Iraq and Somalia already using these approaches.

Factors for successful adaptation

Effectively adapting to climate change requires the fulfilment of several important, although non-exclusive, criteria. In areas affected by legacies of conflict, however, the social capital needed to fulfil them is often lacking. These four issues are significant barriers to successful social adaptation which we believe need to be addressed:

Long-term planning and coordination between different actors on all levels is crucial

International support often focuses on short-term crisis management. While it is important to guarantee access to basic resources after environmental disasters, it is paramount to coordinate peacebuilding efforts and disaster risk responses on the local, national and international level. Designing long-term solutions also helps in avoiding unintended consequences of ad hoc response mechanisms. Moreover, short-term adaptation mechanisms can often only be implemented by those able to afford them, whereas long-term planning can find strategies that serve all.

Awareness of climate security risks can enable effective adaptation

Local authorities often lack knowledge on climate-related security risks. In Iraq, this has resulted in poorly designed policies and opened the door to securitized responses. A lack of water in rural areas has driven migration into urban centres, such as to Basra city. The new arrivals represent an extra strain on the faltering infrastructure and many find themselves in informal settlements without a connection to the service grid. Few find the livelihood and job opportunities they need, and are left with little choice but to enter illicit economies and the proliferating criminal networks. Without understanding the climate risks that drive this phenomenon, adapting to the growing risks becomes much more difficult.

Those most affected by climate change must be represented in its solutions

Marginalised groups in society – those who face the most acute stress – tend to have little sway in governance. This can be observed on a local level in Somalia, where disputes often arise along clan lines. Especially in times of environmental crises, such as droughts, access to ground water wells is highly disputed and during acute emergencies favours the better-off clans that own the land. This has become a significant point of contention among different community cross-sections and fuels already existing grievances among clans. In Somali communities, women and youth are disproportionately affected by the impacts of climate change. But more often than not, they are on the side-lines when peaceful solutions for such conflicts are being sought. Without taking into consideration the perspectives of marginalised groups, however, agreements will almost inevitably fall short.

Intergroup trust is key to escape the zero-sum logic associated with natural resources

Where trust is lacking between groups and individuals alike, avenues for cooperation over contested resources can be slim. In Yemen, communities had to adapt to the wartime fuel shortage by switching from diesel to solar-powered water-pumps, as this has proven to be the only possibility to pump larger amounts of groundwater for agricultural use. Next to lacking water governance, mistrust between local figures and increased competition is exacerbating local conflicts. Tensions between groups continue to stand in the way of local cooperation and recognising the benefits that doing so would entail.

Conflict transformation in climate-affected contexts

Conflict areas face numerous challenges in adapting to climate change, beyond simply meeting material needs. The social and political issues that underpin vulnerability – such as weak governance capacities, long-standing grievances between communities and delicate power balance between key stakeholders – demand conflict transformation and resolution approaches to confront the four barriers to adaptation mentioned above.

Inclusive community participation in dialogue settings can support awareness raising on climate-security risks and create a space for long-term planning and coordination to address them. Participation in dialogue settings – when carefully implemented – can also allow for those communities most affected by climate change to be heard, so that policies adequately respond to their needs.

Simultaneously, climate-focused mediation can build on shared climate change threats and open the door to address social grievances of the affected communities. It can provide an entry point for inclusive dialogue and help to foster coordination between different stakeholders to strengthen social cohesion and trust, not only between different affected communities but also between communities and local authorities. This approach can support the formulation of conflict-sensitive adaptation techniques over shared natural resources to escape zero-sum logic.

Achieving the goals of climate change adaptation means addressing the root causes of vulnerability – root causes inalienable from the conflicts present in these contexts. If we are to support fragile areas in adapting to this present and future crisis, conflict transformation must be part of the conversation.

Media contact

You can reach the press team at:

+49 (0) 177 7052758

email hidden; JavaScript is required