FEATURE | 16 Jun 2020

Prospects for peace amid a global pandemic

Six months into the COVID-19 crisis, we asked our colleagues what the pandemic means for people and countries in conflict. And what are the prospects for peace?

Few of us could have foreseen the scale of the pandemic that would emerge from the first reports of a cluster of pneumonia cases in late December 2019. The unknown ‘novel’ coronavirus that bears last year’s name has made an indelible mark on 2020 – from the grim march of COVID-19’s infection rate and death toll, to the rapid adjustment to ‘social distancing’ and life under lockdown in many places. To date, more than 8 million cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed, resulting in over 437,000 deaths worldwide – and these numbers very likely underestimate the scale of the ongoing tragedy. Beyond the health crisis, the pandemic’s disruption quickly brought on the worst recession since the 1930s.

Six months into the crisis, we asked our colleagues what the pandemic means for people and countries in conflict. And what are the prospects for peace during this time of corona?

Impact of COVID-19 on conflicts

While the coronavirus doesn’t discriminate – it’s affected everyone from frontline healthcare workers to politicians and celebrities – the underlying reality is less ‘egalitarian’.

The COVID-19 crisis compounds the challenges confronting civilians in precarious conflict settings, layering a viral illness on top of the violence and other threats they already face. ‘In many regions COVID-19 and the related lockdown measures could lead to heightened repression, surveillance, restriction of rights, reinforced prejudices against certain groups as well as famine and other struggles over resources,’ notes Anne Kruck, who works on peace education.

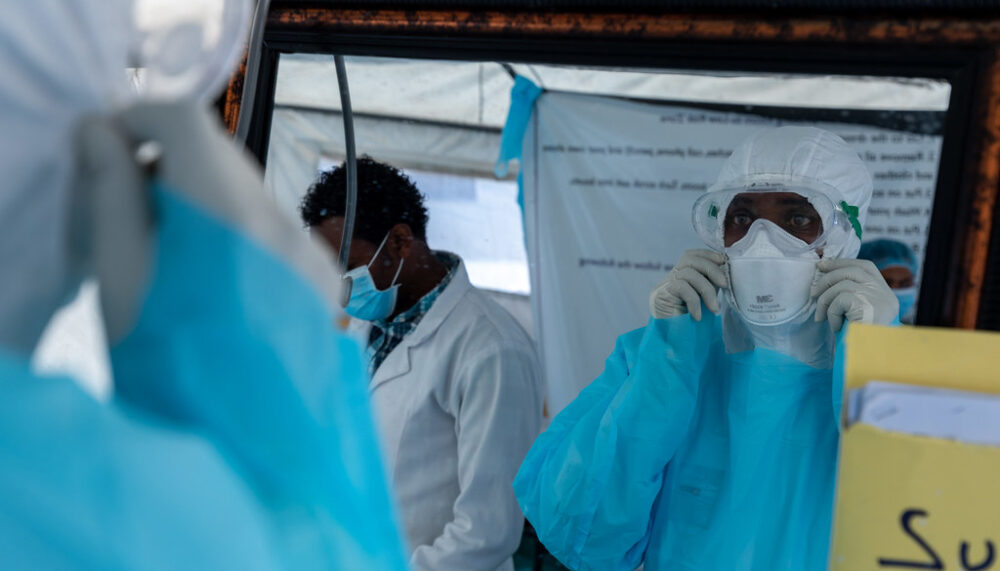

In besieged cities as well as camps for refugees and internally displaced persons, overcrowded conditions make even the basic precaution of social distancing implausible. Already strained humanitarian aid groups working in such settings face an illness that spreads easily and has no vaccine. Meanwhile, healthcare providers in conflict zones have faced many of the same supply shortages that hampered the response even in places not marred by conflict.

There is also the risk that amid the focus on COVID-19, certain conflicts could ‘fall out of the public eye because people are so concerned with themselves,’ says Beatrix Austin from our Conflict Transformation Research department.

Conflicts could escalate if infrastructure collapses, and in the worst cases we could see refugee crises.

Karin Göldner-Ebenthal, Berghof Foundation

‘The time that people normally put into resolving conflict is now going to be focused on surviving, burying family members, trying to stay safe,’ says Janel B. Galvanek of our Sub-Saharan Africa unit. ‘It will lead to more food insecurity, which will lead to more conflict.’

The pandemic is ‘structurally aggravating the conflict in some areas: weak states are becoming even weaker,’ notes Oliver Wils, our Senior Advisor National Dialogues and Dialogue Facilitation. Karin Göldner-Ebenthal from our research team warns that ‘Conflicts could escalate if infrastructure collapses, and in the worst cases we could see refugee crises.’

Donor governments may turn inward as their economies reel from recession, exacerbating difficulties in already stressed states. Yemen, for instance, is facing the prospect of relief money running out even as infection rates rise. Some estimates suggest overseas development assistance could plummet by US$25 billion next year.

Not a reassuring picture. But does the global pandemic also offer an opportunity to deal with conflicts in new ways?

A global ceasefire?

On 23 March, noting the urgency of the pandemic, UN Secretary-General António Guterres called for a global ceasefire: ‘It is time to put armed conflict on lockdown and focus together on the true fight of our lives.’ The ceasefire is needed ‘to help create corridors for life-saving aid. To open precious windows for diplomacy. To bring hope to places among the most vulnerable to COVID-19,’ said Guterres. Numerous states, the African and European Unions, Pope Francis, and many civil society groups (including the Berghof Foundation) are among those adding their support to the call.

Shortly after the call went out, more than a dozen armed groups – including the ELN in Colombia, the National Democratic Front of the Philippines, and the Syrian Democratic Forces – declared unilateral ceasefires. In Yemen the Saudi-led coalition announced a ceasefire, while Turkey and Russia temporarily de-escalated their interventions in Syria. Momentum toward peace – or at least a reduction of hostilities – was gathering.

In early May, hopes for a swift UN resolution on the global ceasefire were dashed at the Security Council, where permanent members China, Russia and the United States squabbled over the wording – including the extent to which the WHO should be praised or condemned for its handling of COVID-19. On 8 May, the US blocked a vote on the ceasefire, leading Oxfam International to call the diplomatic efforts a ‘catastrophic failure’.

With the global call unfulfilled, many of those unilateral ceasefires have since been rescinded, leading to resumed fighting. According to the Norwegian Refugee Council, in the two months following Guterres’ ceasefire call some 660,000 people were displaced by armed conflict. While efforts are still ongoing to enact the global ceasefire, the blockage in the Security Council puts a serious brake on momentum.

Looking ahead: how do we come out of this?

As some countries emerge from lockdown while others grapple with rising infection rates, just how COVID-19 will affect the prospects of resolving some of the world’s intractable conflicts remains to be seen.

‘In many cases, the pandemic affects countries with already deep-seated challenges, violent conflict and multiple crises converging. Yet I hope that in a few cases the urgency of the situation will influence the decisions of conflict parties – at least, to allow for more coordination and cooperation – or even beyond that, that some parties may reconsider the situation and actively engage in a peace process,’ says Sonja Neuweiler of our Middle East and North Africa team.

‘In the past, natural disasters, as devastating as they are, have also created windows of opportunity – for example, the 2004 tsunami that catalysed the peace agreement in Aceh, Indonesia. This opportunity could possibly also change the current situation,’ notes Andreas Schädel, who works on impact measurement and knowledge management. ‘At the same time, situations can worsen when resources become scarce, health systems collapse, and existing inequalities are aggravated.’

In spite of the challenges COVID-19 presents, how we emerge from this crisis is still in our collective control. ‘In these times it is important to show our colours and raise awareness of the potential for non-violent conflict transformation,’ says Austin.

‘Like all viruses, COVID does its utmost to infect as many people as possible. In its staggeringly successful contamination rate, the virus has been aided and abetted by various allies. First of all governments and non-state armed groups who have tried to harness its destruction in order to inflict maximum damage to civilians living in areas held by opponents. And those members of the Security Council who, instead of accepting Secretary-General Guterres’ important call for a global ceasefire, decided to indulge in petty semantic squabbling,’ says Andrew Gilmour, Executive Director of the Berghof Foundation.

Ultimately, violent conflict only harms our response to this pandemic. A willingness to stop fighting, even temporarily, would strengthen global efforts to resolve the health crisis that threatens all of us.

Media contact

You can reach the press team at:

+49 (0) 177 7052758

email hidden; JavaScript is required