Implementing climate-focused dialogue and mediation approaches in practice

Part II of the toolkit on climate-focused mediation and dialogue

Part II offers practical guidance for implementing climate-focused dialogue and mediation approaches. This section introduces four phases – conceptual foundations and design, preparation, conducting the dialogue and mediation process, and implementing its outcomes – aimed at achieving sustainable, community-led and inclusive solutions for climate-related conflicts in Iraq.

Content

- Introduction

- Phase 1: Conceptual foundations and design

- Defining different stages of a conflict, dialogue and mediation approaches

- Integrating environmental and climate change concerns into the process

- Defining the scope and level for addressing climate security risks

- Linking local-level dialogues to other dialogue approaches and climate action at different levels

- Phase 2: Preparation

- Phase 3: Conducting the dialogue and mediation process

- Phase 4: Implementing outcomes

Introduction

Dialogue and mediation can be powerful tools in dealing with conflict constructively. In contexts marked by violence and a complex history of conflict, conducting community dialogues and mediation processes can be particularly challenging. Moreover, integrating environmental and climate change issues into the processes adds an additional layer of complexity. Successfully navigating these challenges therefore requires preparation, facilitation and documentation.

Snapshots: Climate-focused dialogue/mediation efforts by district

Hawija

In Hawija, climate change has negatively affected the availability of water. The dialogue engagement focused on the increased pressure on water resources and the absence of fair and balanced water management, distribution and sharing agreements. At the same time, we addressed the lack of trust in the authorities and between communities, as well as violations such as the installation of illegal water pumps. The dialogue sessions enabled the diverse stakeholders to discuss their views and interests and ultimately reach a water-sharing agreement.

Basra

In Basra, in the south of Iraq, climate change impacts have led to displacement and migration. The loss of livelihoods, growing competition over scarce resources and increased pressure on services due to internal migration and displacement, in combination with weak government capacities, low levels of trust in the authorities and lack of conflict management mechanisms, led to conflict between IDPs and host communities in Zubair (Al-Fidha neighbourhood). Accordingly, the dialogue engagement sought to address conflicts over resources, different tribal/cultural practices and conflict management mechanisms.

Kalar

In Kalar, a region in north-eastern Iraqi Kurdistan marked by long-standing tensions and conflicts, several villages face severe water scarcity. For years, disputes over diminishing water resources, illegal tapping and water allocation violations along the Balajo irrigation channel have exacerbated hostilities, deepening divides and fostering mistrust. The lack of water has contributed to people being displaced from their homes. Climate change has led to more heatwaves and less rainfall, further reducing water availability. Therefore, the need to reduce tensions and increase cooperation among villages along the Balajo irrigation channel has become even more urgent. The dialogue process focused on reducing tensions and increasing cooperation among villages along the Balajo irrigation channel.

Tal Afar

In Tal Afar, climate change has intensified challenges related to water resources. The dialogue engagement addressed the growing pressure on these resources, alongside the absence of fair distribution agreements and efficient resource management. Limited trust in local authorities and weak government capacities have further complicated the situation. The dialogue specifically focused on conflict prevention, aiming to identify and mitigate potential conflicts arising from the intersection of climate change, illegal water wells (used for adaptation purposes) and the exploitation of water resources.

This section introduces four phases to achieve sustainable, community-led and inclusive solutions on climate-related conflicts at the local level in Iraq. Its aim is to offer both conceptual insights and practical perspectives on the topic, drawn from our dialogue and mediation engagement in Kalar (Sulaymaniyah), Al-Hawija (Kirkuk), Al-Zubair (Basra) and Tal Afar (Nineveh) and from interviews with Iraqi dialogue facilitators and mediators.

Four phases to achieve sustainable, community-led and inclusive solutions to climate-related conflicts on a local level:

Phase 1: Conceptual foundations and design

This chapter begins by defining climate-related dialogue and climate-related mediation, assessing when these approaches are most suitable for addressing conflict. It then considers how best to integrate environmental concerns and the impacts of climate change into the dialogue and mediation processes. Next, it discusses how to effectively define the scope and level for addressing climate security risks. Finally, it explores how local-level dialogue and mediation engagement can be linked to broader peacebuilding approaches and climate action across different levels.

Defining different stages of a conflict, dialogue and mediation approaches

We encounter conflict in our everyday lives. Conflict is a clash between opposing ideas or interests with another person or involving two or more persons, groups or states pursuing mutually incompatible goals. Having opposing positions is not negative in itself; indeed, it can be an important driver of change. In other words, it is not the conflict that is the problem, but the way we handle the conflict. It is helpful to understand that conflict escalation happens in different stages in order to address the conflict with the right tool for conflict transformation.

In the early stages of conflict escalation, dialogue is typically used as a means of conflict transformation and resolution. At this stage, dialogue can facilitate a learning and unlearning process. Parties can learn from each other’s experiences and gain new insights into the conflict. Dialogue can also lead to changes in behaviour, as parties begin to see the impact of their actions on others and the wider community, and to changes in mindset and attitude, as parties develop greater empathy and understanding for each other’s perspectives. In addition, through dialogue, a change in perceptions of other parties can be supported. This may involve challenging old assumptions and stereotypes and seeing the other parties as counterparts with valid experiences and perspectives, as well as understanding the underlying issues that are contributing to the conflict. Lastly, dialogue can create space for structural and systemic change. This is about addressing the root causes of the conflict. It may involve changes in policies and structures, creating more inclusive and equitable systems and institutions.

Case study on how dialogue can change perceptions

The case study below offers a glimpse into how a dialogue can lead to changed perceptions among communities and the identification of shared challenges.

Farmers in Dhi Qar and Maysan governorates are experiencing frequent heatwaves and water shortages, leading to crop failures and livestock losses. Many young farmers are abandoning their farms and migrating to urban centres like Basra, where they end up in informal settlements, have very limited access to basic services or job opportunities, and risk being drawn into illicit economies or violence. This urbanisation puts a strain on local services and exacerbates tensions between new arrivals and host communities, often escalating into violence, which local governments struggle to manage due to low levels of trust and limited conflict resolution mechanisms. We began by listening to the needs of the new arrivals and the host communities. Separate sessions were held where members of both groups were able to share their experiences, needs and grievances. It quickly became clear that each had their own specific fears and concerns. Host communities accused new arrivals of bringing tribal conflicts and crime to their city. New arrivals reported facing discrimination and violence. As a next step, we organised dialogues between various communities on a variety of topics, mainly focusing on individual and collective fears and concerns, but also on the effects of climate change and how to support a common approach to these issues. Underlying this approach is the assumption that dialogue can help to overcome these feelings of aversion, foster understanding of diverse perspectives and encourage peer learning. Through dialogue, participants are given the space to work towards a common understanding, break down stereotypes and build meaningful relationships. This dynamic could also be observed among the participants in the dialogue in Al-Zubair. During the dialogue, both groups started to identify shared needs and risks to their livelihoods such as lack of services, unemployment and school kidnappings. Participants also recognised climate change as a shared challenge that exacerbates crop failure and water scarcity and increases the need for electricity, especially for air conditioning in the warmer months. Lastly, women from both communities reported an increased threat of gender-based violence, suggesting that this rise in violence is related to the climate-induced loss of livelihoods and lack of future prospects.

As conflicts escalate to higher levels, mediation becomes more appropriate. By this stage, conflict has intensified, and a multi-partial third party is often necessary to facilitate structured negotiations, manage emotions and guide the parties toward a mutually acceptable agreement. In these fully escalated violent conflicts, when other forms of intervention such as conflict mediation or arbitration are required, dialogue can be useful as a complementary tool.

Through the dialogues implemented by BF and PPO, we are currently trying to counter these incidents which are caused by these big community changes and that’s why we have chosen Al-Fidha neighbourhood as a model for a diverse society. We’re doing so on the assumption that understanding and accepting others is the basic element in confronting tensions and conflicts.

Participant in our dialogue in Al-Zubair

Integrating climate and environmental concerns into the dialogue and mediation process

An integrated approach enables various drivers and root causes of conflicts and tensions to be addressed simultaneously. Starting dialogue sessions with a focus on climate change impacts and environmental concerns can help build trust among stakeholders and create a foundation for broader discussions. This trust-building phase can lead to effective collaboration and sustainable solutions to climate-related risks while also opening pathways for future political dialogue on other issues. By consulting communities on their perceptions of climate impacts, peacebuilding efforts can foster inclusive, locally driven solutions that leverage local knowledge, creating a strong foundation for sustainable peace rooted in community ownership and participation.

An example of an integrated approach

The case study below provides an example of an integrated approach that incorporates climate and environmental concerns into the dialogue and mediation process, thereby improving community relations and bringing an end to trespassing.

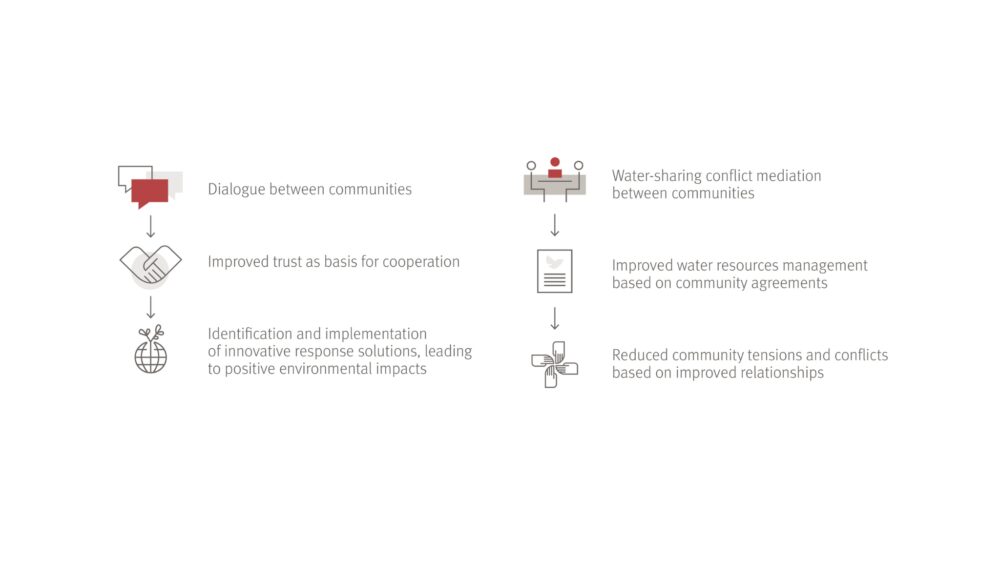

In Hawija, climate change has negatively affected the availability of water. The dialogue process therefore focused on the increased pressure on water resources and the absence of fair and balanced water management, distribution and sharing agreements. At the same time, we addressed the lack of trust in authorities and between communities and violations such as the installation of illegal water pumps.

The first step in the dialogue process focused on improving relationships between the villages involved. Through initial meetings, trust between the communities was regained without yet focusing on solutions. The sessions contributed to changes in behaviour, as those who were acting illegally began to see the impact of their actions on others who live further away from the water source. By encouraging these participants to develop more empathy for others, the mediator/facilitator managed to win their approval for a continuation of the process.

More sessions were then held to brainstorm possible solutions with input from technical experts and the facilitator. In situations where participants are still unable to provide solutions to a specific issue, presenting more information and options for consideration may be helpful. As relationships improved, formulating a shared objective proved to be useful for the continuation of the process. Empowering participants to find their own solutions proved more effective than solely providing a single solution. Therefore, putting an end to trespassing between villages, as this results in inequitable water-sharing, was identified as a joint objective for the process. This facilitated a participatory approach in which a joint solution was adopted.

Local authorities that were willing to address the violations and collaborate with the communities then joined the process. As a sign of their readiness for a jointly formulated water-sharing agreement, the local authorities started a campaign to eliminate illegal access to the irrigation channel and protect local water sources. This, in turn, helped to build trust between the communities and the local authorities.

This integrated approach demonstrates how trust-building and practical action on an environmental/climate-related issue are mutually reinforcing. Without the initial steps to build trust between the communities as part of the process, it would not have been possible to jointly identify a solution and present this to the local authorities. In turn, the local authorities’ efforts to eliminate illegal access contributed to further trust-building and paved the way for more innovative solutions to the water scarcity faced by the communities.

Defining the right scope and level for addressing climate security risks

Climate security risks are the interactions between climate impacts and the security and peace context, which is shaped by social, political and economic dynamics. As a result, the scope and level at which these risks can be addressed vary depending on the specific context.

There are various options to address conflict issues across different dimensions, such as political, social, legal and a combination thereof.

- A social lens focuses on addressing interpersonal relationships, community cohesion and mutual understanding among parties.

- A political lens involves engaging with local and regional authorities or political groups to address governance issues or resource distribution.

- A legal lens emphasises dispute resolution based on laws or agreements on resource rights, land ownership or regulatory frameworks.

Similarly, an engagement can take place at multiple levels: ranging from the very local, such as individual neighbourhoods or villages, to the subnational level, including districts or governorates, and up to the national or federal level. From a conflict transformation perspective, it is often beneficial to complement the engagement at one level with dialogues at other levels, as these can reinforce each other and lead to more sustainable and informed outcomes. Utilising these different approaches helps ensure that processes address climate security risks on the right level and scale. Tailoring the process accordingly ensures that interventions are comprehensive and sustainable, enhancing the prospects for meaningful conflict transformation.

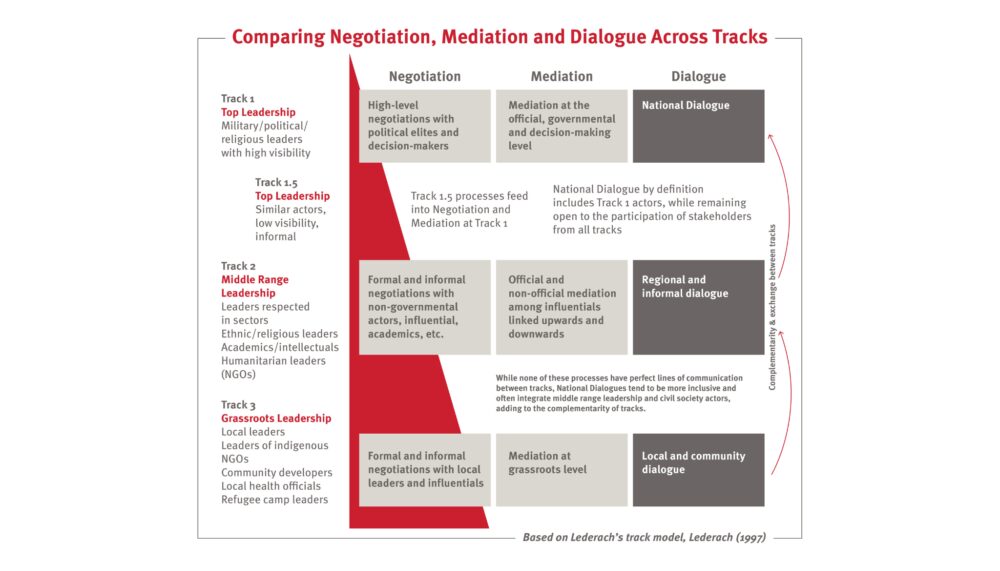

Linking local-level dialogues to other dialogue approaches and climate action at different levels

A multi-track approach involves linking local-level dialogues or mediation engagement with broader processes and climate action at the national and international levels. This approach acknowledged the different levels of society, often referred to as tracks:

- Track 1: Top leadership (high-level policymakers, government officials)

- Track 2: Middle-range leadership (community leaders, NGOs, experts)

- Track 3: Grass-roots leadership (local communities, civil society groups)

Informing national-level governmental stakeholders in community dialogues helps to align local actions with national policies and strategies. These stakeholders can offer guidance, resources and support to community-led initiatives. Gaps between community-level realities and decision-makers can hinder effective climate action. Addressing these gaps is crucial to scaling local solutions, improving coordination, and ensuring that actions taken at all levels are connected and mutually reinforcing. Connecting local dialogues with international organisations brings additional value by leveraging expertise, resources and best practices. International organisations can provide technical assistance, funding and capacity-building support and help to raise awareness of local issues on global platforms.

Practical approaches for linkage

While connecting these levels is often challenging, some practical approaches to achieving this linkage are outlined below:

- Framing community-specific climate impacts as part of larger narratives, such as national security, adaptation strategies or economic stability, can help to ensure that local concerns resonate with national and international interests. However, connecting these issues to sensitive topics like national security can also be challenging and requires careful handling.

- By demonstrating how local-level insights contribute to national climate goals, higher-level stakeholders are more likely to engage and build political commitment to support local action.

- Ensuring an inclusive demographic composition and representation of various political stakeholders allows for a balanced approach that increases the relevance for national stakeholders, facilitating engagement.

- It is often necessary to bridge gaps between the community level and governmental authorities. Convening governmental authorities in multi-level round tables and presenting effective solutions from the local level – such as inviting local stakeholders or sharing insights from local dialogues – can help bridge the gap. These efforts help sensitise national-level stakeholders to the importance of participatory, locally driven solutions and can also help close the gap between policy development and implementation on the ground.

- In addition, involving trusted intermediaries, like local leaders or NGOs, can help bridge these gaps by representing local concerns in higher-level discussions and supporting the multiplication of successful approaches in other contexts.

- Engaging different levels in drafting recommendations for policymaking and decision-making through coordinated efforts supports the exchange of best practices and success stories and helps bridge potential gaps between national policy and local implementation so that national climate security strategies are informed by and responsive to local realities and challenges.

- At times, it may be helpful to involve international organisations directly or keep them in a background role: Involving international organisations directly can be beneficial when their presence lends credibility or opens access to additional resources. However, in sensitive or trust-dependent dialogues, it may be preferable to keep them in a background role in which they provide support without directly participating, to maintain confidentiality and local trust. Additionally, the level of involvement can impact an organisation’s willingness to engage; some may prefer limited roles as advisers or supporters rather than as direct participants. Tailoring their involvement to suit the needs and comfort levels of local participants ensures that international contributions are both effective and contextually appropriate.

- In contexts where participants may be hesitant to speak openly in front of higher-level officials, facilitators can employ methods like private briefings, anonymous contributions or smaller breakout discussions. This enables local voices to be heard without fear of repercussions, preserving the integrity of community insights.

- Facilitating higher-level round tables while also engaging in technical exchanges and informal meetings on different levels improves the implementation of coordination efforts and solution-oriented approaches.

Best practice

In Al-Zubair, Basra, relevant local and national government representatives were involved in the social pact reached as the outcome of the dialogues. Their participation helped to align local actions with national priorities. As the facilitator from Zubair noted, “Involving national government representatives was key to our success. It ensured that our local actions were aligned with national policies and that we had the necessary support.”

Iraq’s evolving climate policy landscape offers valuable insights into how national frameworks can serve as a basis for broader dialogue and coordinated climate action across levels. The development of Iraq’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), along with the subsequent Green Paper, reflects a growing commitment to addressing climate risks and reducing emissions in alignment with international goals. These strategies introduce important policy directions, including regulating well-drilling, promoting efficient irrigation systems, and setting water usage limits.

The Green Paper – developed by the Ministry of Environment in collaboration with other national institutions and supported by international partners – marks an important step in shaping Iraq’s long-term climate vision. It outlines strategic priorities for adaptation and mitigation and provides a foundation for future policy and investment planning.

At the same time, the process highlights the importance of further strengthening the link between national-level strategies and local-level needs, perspectives and dialogues. There is an opportunity to deepen the operational aspects of implementation, enhance coordination between ministries, and create clearer pathways for community-level engagement. Building inclusive governance mechanisms, reinforcing institutional mandates, and ensuring sustainable financing can help translate national climate commitments into effective, locally grounded action.

Phase 2: Preparation

In the second phase, the groundwork for the dialogue or mediation process is laid. This section begins by exploring how to select a location for the process and establish a timeline for the dialogue or mediation engagement. It then examines the steps involved in assembling a team of facilitators. After that, it looks into the identification of participants and strategies for managing third-party involvement. Finally, it addresses the development of an agenda.

Choosing the location and creating a timeline

Depending on the specific location and the participants, dialogues can take place in various settings determined by local conditions and standards. The location needs to be safe, secure and accessible to all participants. The venue should be situated in an area where no party feels disadvantaged. While selecting a location where the impacts of climate security issues are directly visible can add urgency and ground the discussion in lived experience, it can also be beneficial to bring participants to a neutral setting. This distance can help create space for reflection and allow participants to focus more fully on the dialogue itself. When selecting a venue and preparing the setup, it is important to ensure the following conditions are met:

- Participants can make direct eye contact with one another.

- Participants can easily hear each other.

- There are no hierarchical differences in the seating arrangement. However, it may be necessary to consider protocol when engaging higher-level stakeholders, especially if specific requirements have been indicated to ensure their participation.

Usually, U-shaped, semi-circle or conference seating arrangements are preferable.

The timing and frequency of dialogue sessions should be carefully planned to accommodate participants’ schedules and lower barriers to participation. It is often beneficial to hold sessions regularly to ensure continuous engagement. However, depending on the urgency of the issues being addressed, the frequency can be adjusted. Flexibility is important, as climate-related issues can evolve rapidly, necessitating more frequent meetings during critical periods. In addition, allowing adequate time between sessions for participants to reflect, consult with their communities and implement agreed actions is crucial.

A key lesson learned is the importance of aligning session timings with participants' schedules and work commitments. Initially, the dialogue sessions in Al-Zubair were scheduled from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m., but this conflicted with the participants’ work commitments, preventing their attendance. Recognising this issue, we adjusted the timing so that the sessions started after 4 p.m.: “Timing the sessions after working hours and choosing familiar locations were key to ensuring high participation rates. It made it easier for community members to attend and engage in the dialogue process.”

Another key lesson learned is to allow sufficient time between sessions for participants to process information and follow up with their peers to increase ownership. Initially, the general feeling in Al-Zubair was that efforts aimed at making change happen were pointless and that nothing would improve. Through a trust-building process and consistent engagement, this narrative seems to be shifting. The residents now believe they are in a position to make a difference and have moved from a passive stance to actively seeking ways to improve their situation and build on the agreements they have signed. Specifically, young people are actively engaging with peers from other neighbourhoods to discuss the agreement and demonstrate increased ownership. This highlights the importance of allowing sufficient time between sessions for participants to process information and conduct additional meetings with their peers, which has proven crucial for fostering engagement and ownership.

Considering the key skills required by a facilitator

Facilitators help a group communicate effectively and improve their mutual understanding. While the participants in a dialogue or mediation are responsible for the content and outcome of the process, it is the facilitator’s role to ensure that the process remains fair and constructive. It is helpful to choose facilitators who have a good knowledge of the dynamics of the situation. However, it may also be useful to include external facilitators who can offer new perspectives. For climate-related dialogues and mediation initiatives in particular, it is equally important to have experts with technical knowledge of the most relevant climate change issues supporting the processes. Even if not necessarily present in the dialogue or mediation meetings themselves, climate experts can provide valuable support through their in-depth knowledge of climate agreements and dialogue processes. Whether their presence is beneficial depends on several factors, including the complexity of the issues being discussed, the level of technical detail required and the sensitivity of the dialogue environment. In cases where detailed technical input is critical to the outcomes – such as discussions on resource management or adaptation strategies – it is preferable to have climate experts present to provide real-time insights. However, in more sensitive contexts, where the presence of outside experts may inhibit open communication, experts can offer guidance beforehand or consult with facilitators before, between and after sessions. Our experience shows that involving climate experts indirectly in sensitive cases helps to achieve a balance between offering access to the necessary expertise, generating options for solutions and maintaining a comfortable space for participants to express their views freely.

While having a team of facilitators can be beneficial, this is not always possible. The key skills and requirements a facilitator or team should have are outlined below:

- Multi-partiality: Integrating opposing perspectives into a peaceful settlement of conflict requires that all sides are equally heard and taken into account. More than being impartial, we approach all parties with openness, trying to understand their underlying interests and motivations. (See Berghof's vision)

- Facilitation tools: Certain facilitation tools such as active listening, reframing and summarising support facilitators in creating a safe space for dialogue, helping participants to express themselves, understand others, and find common ground. These methods can assist in managing tensions and guiding the mediation and dialogue process toward shared outcomes (see facilitation tools within this toolkit for further guidance).

- Team awareness: Working in mixed facilitation teams, including insider and external mediators, climate experts and support staff to observe group dynamics and facilitate individual interactions outside the dialogue sessions, can effectively facilitate dialogue and mediate agreements between conflict parties. Working collaboratively with an awareness of each other’s strengths and weaknesses as facilitators builds a strong and effective team.

A good facilitator must maintain impartiality and respect, treating every participant with equal openness. They should manage group dynamics carefully, such as addressing imbalances in discussions, to keep the focus on solutions. Effective facilitators actively listen and ask consistent questions to ensure diverse perspectives are heard, demonstrating that each participant’s input is valued. This approach fosters trust and encourages active engagement from everyone involved.

Quote from facilitator

Inviting participants and dealing with third parties

The impacts of climate change in Iraq are not uniform across population groups. Vulnerability varies significantly based on factors such as age, gender, disability and socio-economic status, presenting both challenges and opportunities for community resilience and change. The consideration of specific vulnerabilities is important to ensure meaningful representation and a holistic approach to dialogue and mediation engagement. Inclusivity and participation are essential in peacebuilding efforts, as they help address social grievances of exclusion and marginalisation and increase a sense of ownership and responsibility, thereby enhancing the sustainability of solutions.

Recognising and addressing vulnerabilities can also be a catalyst for positive change within communities. By identifying and targeting the unique needs and vulnerabilities of different groups and leveraging their distinct capacities and knowledge, communities can develop more comprehensive and effective adaptation strategies. This process not only builds resilience but also promotes social cohesion. The following vulnerabilities provide a basis for understanding how to approach engagement in an intersectional way and ensure inclusivity and meaningful participation:

Gender-specific vulnerabilities

Women face heightened vulnerabilities due to unequal access to resources, traditional gender roles and limited decision-making power. For instance, women are often disproportionately affected by climate change, particularly if their livelihoods are tied to agricultural and household roles. Climate-induced economic hardships can also lead to increased domestic violence, further exacerbating their vulnerability. Additionally, climate-related displacement significantly impacts women more than men, as it disrupts their stability and poses unique challenges related to hygiene and mental and physical health. On the other hand, men might experience increased militarisation and conflict as a direct result of resource scarcity and economic pressures. Empowering women in decision-making, promoting access to resources, and addressing gender-specific needs in adaptation strategies are essential. This includes ensuring that women’s voices are heard in local governance and climate resilience planning, as well as providing targeted support for women-led initiatives that enhance community adaptation and resilience. In addition, gender scholars have found that gender (in)equality is strongly associated with instability and conflict: the International Union for Conservation of Nature has demonstrated that countries with significant gender inequality scores are more likely to face instability, conflict and heightened vulnerabilities to climate issues. Gender issues therefore have a key role to play in the formulation of effective policies for adaptation, mitigation and conflict resolution.

Youth and livelihood vulnerabilities

Young people in agricultural communities are particularly at risk of losing their livelihoods due to climate impacts, as they often work in sectors that are highly susceptible to environmental changes, such as agriculture and informal labour. These economic pressures, combined with limited alternative opportunities, can lead to increased migration and displacement as young people seek stability and viable livelihoods elsewhere. This demographic shift can weaken community structures and lead to loss of cultural heritage and social cohesion. To mitigate these risks, creating employment opportunities, strengthening education systems and empowering youth participation in climate adaptation and resilience-building efforts are critical. Youth engagement helps not only in harnessing their innovative potential but also in ensuring long-term sustainability of climate actions.

Marginalised groups

Marginalised groups, including ethnic minorities and people with disabilities, often face exclusion and discrimination, which increases their vulnerability to climate change. These groups may have less access to the essential resources, information and support systems needed for an effective response to climate challenges. It is crucial to address their specific needs and actively involve them in adaptation efforts. Inclusive strategies that prioritise equity and social justice can help to reduce vulnerability and foster resilience among the most affected populations.

When selecting participants for an inclusive dialogue, it is critical to consider these vulnerabilities and involve a diverse range of stakeholders, including community representatives, civil society organisations, tribal and religious leaders, and government agencies. Ensuring the meaningful representation of women, young people and vulnerable populations enhances the comprehensiveness, sustainability and legitimacy of solutions.

Equally important is the involvement of influential actors and the establishment of focal points to facilitate communication and coordination.

- Influential actors play a critical role in the success of dialogue processes. Primary influencers hold formal authority and can make decisions, while secondary influencers, despite lacking formal positions, exert significant influence within their communities. Engaging both types of influencers helps to ensure broader acceptance and implementation of dialogue outcomes.17 Influential stakeholders should be managed closely and carefully as they are often conscious of their privileges. It is therefore important to create conditions in which their authority cannot be used for personal gain.

- Focal points support liaison between the dialogue organisers and their communities. They help to build trust, facilitate communication and ensure that all voices are represented. Establishing focal points for different community groups can enhance the inclusivity and effectiveness of the dialogue process.

- A stakeholder mapping may prove to be essential in identifying the primary and secondary influencers and focal points.

Examples from our project

As part of the consultative dialogue preparation in Al-Zubair, Basra, the facilitator identified key community representatives who could provide entry points to the broader community. They established focal points for different community groups, such as women, men and young people, to ensure appropriate selection and representation. During a reflection workshop, the facilitator emphasised, “The selection of participants should be based on a set of criteria tailored to the community’s context. Involving influential key actors ensures that the dialogue process is grounded in local realities.”

In Hawija, Kirkuk, the facilitator faced a challenging request from one of the key stakeholders regarding the logistical arrangements for the dialogue location. The facilitator addressed this by drawing on the support of other influential actors to mediate the request and manage the expectations of local authorities. The facilitator noted: “Transparency and direct communication were crucial in addressing the demands of key stakeholders. I also relied on influential actors to mediate and pressure the key stakeholders to compromise, which was time-consuming but effective.”

In Tal Afar, Nineveh, the inclusion of religious leaders in the sessions was crucial. These leaders took up the dialogue issues at Friday prayers, which significantly influenced community participation and support. As the facilitator from Tal Afar explained, “Having religious leaders involved was important because they have a significant influence on the community. Their endorsement of the dialogue process during Friday prayers helped to legitimise and promote the dialogue.”

Developing an agenda

Dialogues and mediations are rarely singular events, but part of long processes that can take weeks, months or even longer, depending on the topic and the level of conflict. The facilitator’s role is to dedicate enough time within each session and between sessions to guide participants through the various phases of the process.

Setting an agenda for dialogue sessions requires careful planning, considering both the participants’ needs and the nature of the conflict. The facilitator drafts the agenda for each individual session, as well as for the overall process. To ensure that the participants' priorities are reflected, it is essential to involve them in the agenda-setting through a consultative process, gathering their feedback and input. There are different strategies for designing an agenda:

- A gradual approach, starting with less contentious issues, can help build trust and momentum. Beginning with topics on which at least partial agreement can be reached fosters a positive atmosphere, setting the stage for deeper engagement on more complex issues. For example, in a dialogue related to climate change, the facilitator might start with less contentious topics like the importance of local environmental conservation practices or the benefits of early warning systems for natural disasters.

- Addressing the most challenging issues first can sometimes be necessary, especially if participants feel strongly about these issues or refuse to engage if the most contentious topic isn’t addressed at the beginning. For example, during a process involving agricultural communities, farmers may be most concerned about the immediate impact of droughts on their livelihoods. If this topic is not brought up at the start, they may be unwilling to participate in discussions about climate adaptation strategies.

A deep understanding of the context is needed to determine which approach is most appropriate for the given situation. While careful planning is essential, it is equally important to stay flexible, especially in situations where participants may react strongly to an issue or provide feedback that requires adapting the agenda. The following phases can help as a guideline for the facilitator in developing both individual sessions and the overall process:

Getting to know each other

In this phase, the facilitator establishes jointly with the participants the ground rules for respectful communication. Participants are then encouraged to present their perspectives and needs. For example, in a dialogue related to climate change and environmental issues, participants may express concerns about how diminishing water sources affect their livelihoods. To help organise the discussion, facilitation tools such as summarising statements and visualising issues (e.g. using maps to highlight water sources or areas affected by climate change) can be used.

Deepening of understanding and sharing of perspectives

A key aspect of this phase is to acknowledge and address underlying feelings, concerns, fears and needs of all parties. This emotional layer often plays a significant role in how people engage with each other and the issues at hand, so understanding these deeper concerns can foster empathy and trust. For example, in a dialogue related to water scarcity, participants could conduct a field visit to the areas most affected by climate change to see how it affects the communities’ livelihoods. The facilitator can use tools such as open-ended and circular questions, reframing and mirroring to help participants reflect on their own and others’ perspectives.

Generating inclusive options

At this stage, the focus shifts to generating potential solutions, with an emphasis on creating an open space for brainstorming. During this phase, it is crucial not to evaluate options too early, as the goal is to encourage creative thinking and the generation of a wide range of alternatives. For example, in mediation and dialogue processes related to water scarcity, participants might brainstorm alternatives such as modern irrigation systems, adaptation plans and complaint mechanisms. Facilitation tools such as brainstorming and guiding participants to explore alternatives without immediately evaluating them are key to this phase. Expert inputs can help the process by providing additional and informed options.

Discussing and evaluating options

In this final phase, the focus shifts to discussing and evaluating the options that have been generated. Before this discussion, it is important to prepare a list of criteria that will help in evaluating the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed solutions. For example, in a process between farmers and local governmental authorities, the group might evaluate the potential solutions such as introducing drought-resistant crops, adjusting planting schedules, or creating water conservation systems. The criteria for evaluation might include factors such as cost, ease of implementation, potential for increasing food security, and environmental stability. This step is crucial for narrowing down the alternatives to identify the most viable options, ensuring that the solutions are practical and widely accepted by the participants.

In Kalar, Sulaymaniyah, respect and active listening were emphasised to build results and allow space for free expression. Equal opportunities for engagement encouraged all participants to get involved in the discussions. The facilitator from Kalar noted, “Respect and active listening were imperative to build trust and encourage participation. Allowing space for emotional expression was also important, especially in emotionally charged cases.”

Phase 3: Conducting the dialogue and mediation process

In the third phase, the dialogue and mediation sessions are conducted. This chapter focuses on techniques and methods for facilitating a dialogue or mediation process and supporting communities with concrete initiatives on the ground.

Exploring core communication skills and methods

Facilitation tools and techniques help to create an environment conducive to open and constructive dialogue. A well-facilitated process ensures that participants feel heard, respected and actively engaged in addressing shared challenges. This chapter provides key facilitation tools and methods that support a dialogue or mediation process. It addresses essential communication skills for facilitators and strategies to structure and guide communication effectively.

A facilitator helps parties to understand each other better and moves the dialogue from an exchange of positions to an exploration of underlying fears or needs.

- When a facilitator listens and restates information or ideas using their own words – through paraphrasing – it can motivate the speaker to elaborate further or feel acknowledged for what they have shared.

- Reframing is another basic tool for facilitating conflictual issues. The facilitator reframes statements that may carry hostile or biased messages to make them more acceptable to others.

- Additionally, when participants provide long or detailed statements, summarising can help document where the process stands and ensure the discussion stays focused.

- Asking open-ended questions encourages participants to think in more depth about their messages and helps get to the core of a participant’s wants, fears or visions.

- Facilitators can also use body language to show their openness, empathy and commitment to the topics raised and discussed.

As a facilitator, it is essential to provide space for anger and frustration. If you don’t allow time for these emotions to be expressed, they can influence the agenda. I don’t stick rigidly to the agenda’s timing if I see that this is necessary. Also, in some sessions, participants might sit in a way that suggests they are controlling the scene. Body language can greatly influence the setup. Therefore, it is crucial for the facilitator to have a knowledge of the power dynamics and the individuals who are present.

Quote from facilitator

Facilitation methods are tools to organise communication effectively, ranging from free-flow conversations to structured approaches. The choice of method depends on the purpose, mandate, timeframe and context of the dialogue, as well as group size, power imbalances and practical aspects like the venue:

Free-flow discussions

For example, free-flow discussions work well for smaller groups addressing community concerns, such as the impact of droughts on livelihoods, because the informal setting encourages open sharing of personal experiences on a broad issue that affects everyone. As long as the topic is not so sensitive that it prevents participants from acknowledging others’ perspectives, it can foster a shared space where individuals connect through their experiences and feel encouraged to contribute.

Round-robin discussions

In more complex settings, structured approaches like round-robin discussions ensure that all voices are heard. This can be particularly useful in dialogues where tensions arise – such as between host communities and climate-displaced communities accusing each other of insecurity or violence – by creating space for each participant to share their perspectives.

Breakout groups

Similarly, small breakout groups encourage brainstorming and help prevent dominant voices from taking over the discussion, thereby making it easier for some people to speak. These groups also allow for deeper, more focused exploration of complex issues. For instance, in a dialogue about water scarcity, smaller groups can explore specific solutions such as improving irrigation systems or implementing rainwater harvesting techniques. Discussing these complex problems in smaller breakout groups can lead to a wider range of potential solutions and more inclusive participation.

Flexibility and adaptability

Flexibility and adaptability play an important role in facilitation, allowing facilitators to respond to the dynamic nature of dialogue and mediation processes. It can be helpful to adjust approaches based on participants’ needs or feedback. This may involve adapting facilitation tools, formats or agendas as needed to maintain engagement and achieve desired outcomes.

In Zubair, Basra, breakout groups were used to collect vital information about the depth of the tension, the linkages between climate, displacement and conflict, and their impact on social cohesion, when initial sessions were ineffective. The facilitator from Zubair explained, “Breakout groups proved effective in collecting information when the initial format wasn’t working. Additionally, having two facilitators allowed us to cover gaps in each other’s knowledge and enriched the dialogue.”

Linking climate action and other peacebuilding efforts with the dialogue and mediation processes

To enhance the sustainability and impact of climate-related dialogues and mediation efforts, conflict-sensitive initiatives addressing community needs can complement dialogue and mediation processes. These initiatives may vary in form and size, depending on the dialogue and mediation process and the identified needs of the participants. During the processes, it became evident that supporting the development of concrete solutions and practical climate-related agreements through inclusive dialogues enhances the acceptance and commitment by local authorities and communities. In addition, it became clear that supporting the concrete implementation of identified solutions in climate-related agreements with small-scale initiatives further enhances the agreement’s sustainability and compliance by helping to address communities’ immediate and urgent needs.

The following ideas were generated by the participants in the dialogue and mediation engagements, showing how ideas can be developed and what they might look like:

Building capacities

Capacity-building activities equip participants with the skills and knowledge needed to implement dialogue outcomes and adapt to changing conditions. These activities can include training workshops, technical assistance and peer learning exchanges.

- In Kalar, capacity-building training on advocacy, climate-conflict mediation and action planning complemented the dialogue process. Participants gained practical skills to implement agreed actions and became agents of change within their communities.

- In Tal Afar, capacity-building training focused on climate-conflict mediation, equipping stakeholders with tools to address climate-related tensions. As the facilitator from Tal Afar explained, “The capacity-building training was essential for empowering the community. Participants learned practical skills and strategies that they could apply to adapt to climate change-related tensions and conflicts.”

- The facilitators and experts also reported that peer exchanges and expert support ensure that agreements effectively address identified conflicts, mobilising communities to engage and leveraging diverse expertise.

Raising awareness

Awareness-raising activities build broader support for dialogue outcomes and ensure that the wider community is informed and involved, helping to build trust and ownership. These activities can include publicity campaigns, field visits, community meetings and participatory planning processes.

- As the facilitator from Al-Zubair explained, “The awareness-raising campaigns were crucial for building community support. They helped to inform the wider community about our dialogue.”

- Given the widespread misinformation and lack of awareness about climate change, as observed across multiple operational locations, a short film addressing the critical issue of climate change was produced. The film serves as a call to action, urging citizens to be more conscious of their water usage.

- As part of the project, we also organised joint field visits by upstream and downstream communities to enable them to gain a shared understanding of the impact of water-sharing practices.

Engaging in rehabilitation efforts

Rehabilitation activities can be crucial for addressing communities’ immediate and urgent needs for climate adaptation and mitigation. These activities can involve infrastructure development, technical assistance in water management systems and reconstruction.

- In Hawija, the water directorate provided technical support to maintain the pumps for a water station and prepared a submersible well pump, connecting it to the water network. This initiative was jointly developed during the dialogue engagement. The water pump now serves a population of 7,000 and has provided access to water for the most remote village, which previously lacked access due to weak water flow and maintenance issues.

Best practice and lessons learned to implement initiatives in a conflict-sensitive way

Participatory: Implementing initiatives selected in a participatory way by the community fosters a stronger sense of ownership and commitment to the outcomes of dialogue processes. It also creates opportunities for collaboration among community members, local authorities and locally engaged non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Inclusive stakeholder engagement – including government agencies, community leaders, civil society organisations and affected communities – helps build trust, amplify diverse voices and enhance the initiative’s legitimacy.

For example, the Hawija water directorate provided technical support to maintain the pumps at a local water station, prepared a submersible well pump and connected it to the network. This maintenance initiative was identified and developed during the dialogue process, ensuring sustainable access to water for various villages. The inclusive approach, involving government representatives, community leaders and local actors, fostered broad support for the initiative. By designating the water directorate as the implementing agency, the initiative fostered local ownership and improved coordination between the directorate, the municipality and the mayor. The mayor’s involvement facilitated discussions across various departments and mobilised resources to address key issues. As a result, the water pump now serves a population of 7,000 and provides water access to the last village in the area, which previously lacked access due to weak water flow and poor maintenance. As the facilitator from Hawija explained, “Engaging all stakeholders was key to our success. It helped to build trust, ensured that all voices were heard and enhanced the legitimacy of the dialogue approach.”

Flexible: By maintaining flexibility, communities involved in dialogue and mediation processes can better identify and prioritise concrete initiatives – such as small-scale rehabilitation projects – that support the implementation of certain outcomes in mediated agreement. This approach also helps to ensure that these initiatives remain responsive to local priorities.

For example, allocating resources or creating opportunities to partner with others can support follow-up activities without prescribing their exact form in advance. This empowers communities to shape the initiative based on their specific needs – whether that means conducting advocacy training on agreed clauses, addressing technical or infrastructure challenges, or introducing new agricultural seeds as part of climate action. Leaving the exact focus to be determined locally allows the initiative to remain adaptable and more closely aligned with community priorities.

Adaptable and context-informed: An adaptive approach allows stakeholders to respond to changing conditions and to new information developed and received during the dialogue and mediation processes. This helps to ensure that initiatives remain relevant and respond effectively to changing needs, conflict dynamics and climate patterns. Understanding the specific context in which the initiative is implemented helps to avoid unintended consequences that could reignite tensions or exacerbate vulnerabilities. For example, even when activities are agreed in dialogue, implementing them may still require additional assessments to ensure a conflict-sensitive approach.

For example, in Kalar, the construction of a well providing 98 families across two villages with access to groundwater required ongoing coordination with authorities and relevant directorates. As the facilitator from Kalar explained, “Flexibility and adaptability were crucial for the success of our initiative. Regular coordination allowed us to make necessary adjustments and ensure that our initiative remained relevant and effective.”

Phase 4: Implementing outcomes

In the fourth phase, the dialogue or mediation process comes to an end. This section provides insights on how to reach potential outcomes integrating climate and environmental concerns into the process and focuses on specific steps after the conclusion of a mediation or dialogue process:

Reaching agreements or a change

Outcomes of dialogue and mediation processes that integrate climate and environmental concerns can include formal agreements and changes in relationships and attitudes among participants:

Formal agreements are tangible outcomes of mediation processes, serving as a roadmap for future actions and commitments. These agreements often address specific issues identified during the mediation process and outline the roles and responsibilities of different stakeholders. Formalising agreements can enhance accountability and provide a clear framework for implementation.

Read more

- A consensus on an agreement can be reached in an active way by the facilitator asking if participants agree to a proposed solution. Everyone has to agree verbally or by raising their hand. It can also be reached in a passive way. This means that an agreement has been reached if no one rejects it. This can be a powerful way of reframing an agreement as some parties – for political or face-saving reasons – might be unable to actively engage.

- In many cases, agreements are not legally binding. However, the strong element of community ownership plays a vital role in ensuring their sustainability and compliance beyond the mediation process. It is essential to ensure that the agreement aligns with constitutional principles and is legally sound in order to make it more sustainable.

- Agreements provide a framework for parties to commit to key actions, shared values and mechanisms.

- Building on this framework, action and work plans help translate the objectives of mediation and dialogue processes into specific actionable steps. While agreements outline the commitments or mutual understanding reached (“what has been decided”), action or work plans break them down into concrete tasks, timelines, responsibilities and resource needs (focus on the “how”). For example, an agreement might state a commitment to equitable water-sharing, while the action plan specifies steps such as scheduling distribution, assigning monitoring roles, and setting up feedback mechanisms. Action and work plans thus ensure that agreements are implemented effectively.

- Incorporating adaptive strategies into agreements provides the flexibility needed to respond to future climate impacts, ensuring the sustainability of outcomes and enhancing resilience. This involves flexible planning, continuous monitoring and the ability to adjust actions as conditions evolve. For example, in a dialogue process focused on water management, communities may agree to adjust water-sharing schedules based on real-time rainfall data, allowing them to adapt to changing climate patterns. Adaptive strategies acknowledge the uncertainty of climate change and emphasise continuous learning and adjustment.

Discover more examples from different regions of Iraq:

Insights from Hawija

In Hawija, Kirkuk, participants successfully reached an agreement on water-sharing practices, which helped to mitigate conflicts over water resources and established a cooperative framework for managing water scarcity: “The water-sharing agreement was a significant outcome. It formalised commitments from different stakeholders and provided a clear framework for cooperation.” In the case of the Hawija agreement, the community committed to several key actions, including eliminating water violations, resolving water usage issues and other community problems by peaceful means, resorting to legal action only if peaceful solutions proved unattainable, activating a reporting mechanism, committing to proper waste disposal, coordinating water distribution and forming an oversight committee. In a next step, the agreement was formalised at a public signing ceremony attended by key stakeholders, including local authorities, community and tribal representatives, and members of the broader community. While not being legally binding, the significance of this agreement lies in its representative nature – bringing together all disputing parties to collectively outline and accept their respective responsibilities arising from the mediation process.

Insights from Al-Zubair

In Al-Zubair, Basra, the dialogue process resulted in a social pact in which parties committed to foster social cohesion and developed recommendations relating to climate change. Building on that, an action plan was developed to address specific concerns raised during the dialogue sessions. The plan included measures such as improving the security presence in identified locations and promoting cross-community social cohesion in some of the schools. According to the facilitator from Al-Zubair, “The action plan was crucial for implementing the agreed solutions. It provided a clear roadmap and helped to ensure that everyone was on the same page.”

Insights from Tal Afar

In Tal Afar, the dialogue process included the development of an adaptive water management strategy that allowed for adjustments based on seasonal water availability and changing climate conditions. The facilitator from Tal Afar explained, “The adaptive water management strategy was designed to be flexible and responsive. It allowed the community to adjust their actions based on real-time conditions and new information.”

Changes in relationships and attitudes are often intangible but powerful outcomes of dialogue processes. While not always immediately visible, the shift towards mutual understanding, trust and improved communication fosters collaboration and contributes to more sustainable solutions.

- A key outcome of dialogue processes is the establishment of mutual understanding between previously conflicting parties. For instance, in Al-Zubair, communities recognised climate change as a major driver of displacement and migration, reducing blame between internally displaced persons (IDPs) and host communities. This awareness also created space for discussions about shared challenges, such as a rise in gender-based violence linked to lost livelihoods and concerns over inadequate security in schools. By framing climate change as an external factor, integrated agreements can reduce blame and defuse pre-existing tensions, acting as a connector between people and creating a positive environment for dialogue.

- The dialogue process in Kalar improved relationships among different community groups and between local authorities and communities, leading to greater cooperation. Local authorities and community representatives collaboratively identified the villages of Dara and Fath Allah as being most in need of new wells to address critical water shortages. This inclusive and conflict-sensitive process ensured resource allocation aligned with actual community priorities, ultimately benefiting nearly 100 families. As the facilitator noted, “One of the most important outcomes was the change in relationships. Participants began to see each other as partners rather than adversaries, which was a significant step forward.”

Measuring the impact of the engagement

In order to gain a better understanding of the added value of integrating climate security risk analysis into peacebuilding efforts and to constantly adjust and adapt the programming, it is important to apply tools to monitor and evaluate the impacts generated and extract learnings. This section includes methods to use for MEL on climate-related dialogue and mediation interventions, and how to apply them.

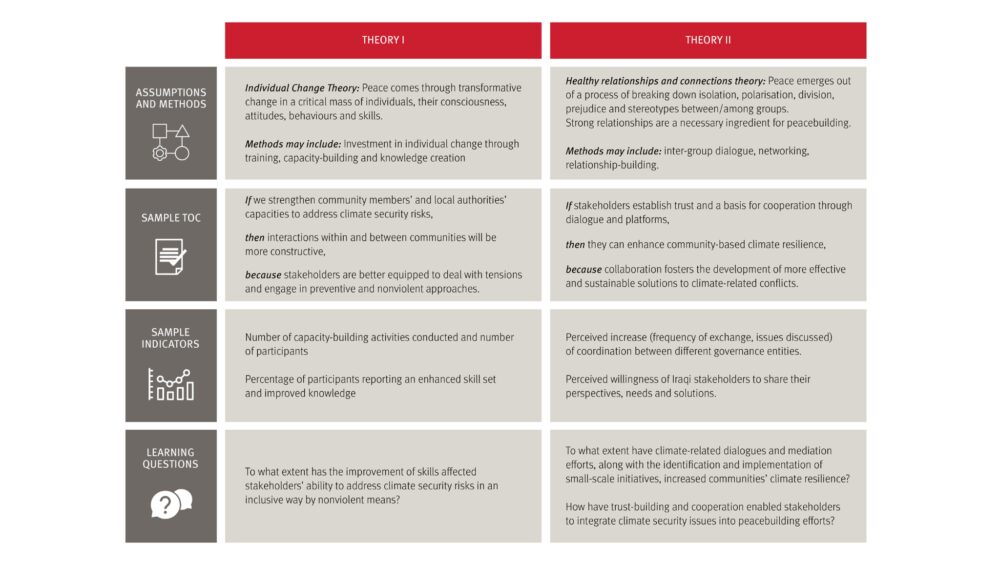

Theory of Change (ToC) for climate and peace

A Theory of Change describes how a project aims to make change happen, thereby providing a framework for understanding how the engagement leads to desired outcomes, such as reduced conflict and improved resilience: “A Theory of Change is an explanation of how and why an action is believed to bring about its planned objectives, i.e. the changes it hopes to create through its activities, thereby revealing underlying assumptions.” Connecting the ToC with indicators is helpful when planning an impact assessment. Learning questions can be supportive in guiding the evaluation and identifying necessary adjustments to the project’s theory of change and logic.

The following table provides a sample ToC and indicators, connecting them to their underlying assumptions and methods. It also includes learning questions which integrate climate and environmental security into peacebuilding ToCs and can be used as examples.

Outcome Harvesting

This method is a monitoring and evaluation approach that helps us understand how our project is contributing to changes in a complex and dynamic context where relations of cause and effect are blurred. Outcome harvesting collects evidence of changes in the "behaviour writ large" of one or more social actors influenced by our projects. Specifically, it looks at who has done what differently, when, where and why, with a focus on new behaviours, events, actions, policies, announcements or developments. By collecting evidence of what has changed, we can work backwards to determine whether and how our project has played a role in those changes.

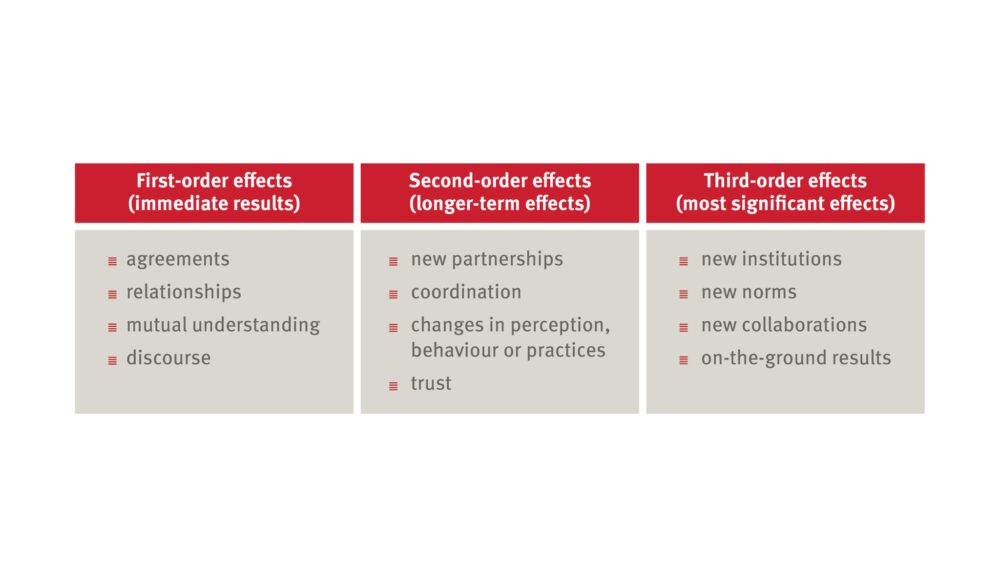

Read more

The aim is to capture all possible outcome-level results, beyond those outlined in the project logframe, and to continuously monitor our project's impact to inform ongoing improvement. By capturing both intended and unintended outcomes, outcome harvesting allows us to refine our approach over time and identify any negative consequences that may need to be addressed. The Outcome Statements can then be analysed against the process’s objectives and activities and their immediate, intermediate or long-term impacts (first-, second-, and third-order effects).

Example 1: A participant in the Zubair dialogue session identified climate change as a key driver of displacement and migration. This served as an entry point for a discussion about climate change as a factor in the conflict, which in turn facilitated a reduction in the mutual accusations between IDPs and host communities. [First order – mutual understanding]

Example 2: The mukhtars (local community leaders) in Kalar and representatives of government departments established contact with their respective peers and opened communication channels via WhatsApp to address water shortages cooperatively. [Second order – changes in practices; coordination]

Example 3: Local authorities in Hawija started a campaign in February 2023 to remove illegal access to a water channel and protect local water sources. This is a first step towards dialogue and building trust between local communities and local authorities on a water-sharing agreement. [Third order – on-the-ground result]

Perception surveys

Perception surveys enable an inclusive, participatory and transparent approach to evaluation. These surveys can be designed in collaboration with partners and external stakeholders, ensuring that the methodology is sound and context-sensitive, based on a do-no-harm approach. Surveys can be conducted at various stages and include pre- and post-activity assessments, needs assessments before workshops, or even longitudinal studies to monitor key variables over time. While outcome statements measure behavioural changes, these surveys provide valuable quantitative data that complement the qualitative insights gained, offering a more comprehensive understanding and evaluation of the impact. Through perception surveys, climate and environmental impacts, along with peace and conflict impacts, can be measured interactively. This approach makes it possible to monitor and assess communities’ climate resilience at different points in time.

Example questions

- How confident are you that your community can adapt to future climate-related challenges such as droughts or floods? (1: not confident at all; 10: extremely confident)

- To what extent do you agree with the statement: “Climate change impacts, such as droughts, floods and sandstorms, are a threat to our community”? (1: not at all; 10: to a very high extent)

- How confident are you in understanding the linkages between climate change, conflict, peace and security? (1: not confident at all; 10: extremely confident)

- How confident do you feel in your ability to facilitate dialogues on climate-related/environmental topics and conflicts? (1: not confident at all; 10: extremely confident)

Sample analysis of perception survey from the project

- In Tal Afar, participants’ confidence in facilitating dialogues on climate-related conflicts improved from 7.1 to 8.4, i.e. an 18.3 per cent increase.

- In Kalar, participants demonstrated an improved understanding of the linkages between climate change, conflict, peace and security, with their average rating rising from 6.8 to 8.6, i.e. a 26.47 per cent increase. Additionally, their confidence in facilitating dialogues on climate-related and environmental topics and conflicts improved from 5.6 to 8.4 – a 50 per cent increase.

- In Hawija, the training resulted in an increase in participants' understanding of the climate-conflict nexus from an average rating of 6.5 to 7.8. This represents a 20 per cent increase in their understanding. Additionally, the training led to an increase in participants’ confidence in facilitating dialogue on climate-related and environmental topics from an average rating of 7.1 to 8.2, which represents a 15.49 per cent increase in their confidence.

Best practice

The quantitative approach and the survey itself rely on self-assessment, which leaves room for bias or subjective interpretation. As a result, the survey findings sometimes did not show a significant increase, or even indicated a decline, in confidence and capacity levels. However, this does not necessarily mean that the training was unsuccessful. Including a few open-ended questions in the survey may be helpful in identifying trends, even if the quantitative data does not yield meaningful results. For example, when comparing pre- and post-survey results, the participants demonstrated a consistent understanding of the linkages between climate change, conflict, peace and security with an unchanged rating of 6.4 both before and after the training, while their preparedness for advocacy efforts remained unchanged at 9.0. When examining the responses to the questions about how dialogue and mediation on climate change and the environment can help transform conflicts and whether all people are equally affected by climate change, several trends emerge from the post-survey results. The responses are 1) more well-founded and precise, 2) provide more details or specific examples, and 3) include answers where none were provided previously. This suggests that, although the quantitative results — based on participants' self-assessment and perception — did not show a significant change, especially regarding the level of confidence to engage in advocacy and the understanding of the climate-security nexus, the qualitative responses indicate a deeper understanding and enhanced skill set.

Continue reading

Want to learn more? Go back to Part I on how to analyse climate-related conflict risks.

Part I (Analysis) Back to the main page

Get in contact

What do you think about the toolkit and how do you plan to implement it within your project?

We would like to hear from you. Please, contact us via email.

Thanks for your interest

If you find this publication useful, please consider making a small donation. Your support enables us to keep publishing.