Analysing climate security risks

Part I of the toolkit on climate-focused mediation and dialogue

Part I outlines the process of identifying and analysing climate-related security and conflict risks using the Weathering Risk methodology. This section describes the mapping process in three phases – design and planning, data collection and interviews, and analysis – and explains how to generate and identify entry points for climate-related mediation and dialogue at the local level.

Introduction

The interplay between climate change impacts, peace and security presents a multi-faceted challenge, particularly in regions like Iraq, where entrenched conflict, long-standing grievances and deep societal mistrust persist.

According to the ND-GAIN matrix, Iraq is the 81st most vulnerable and the 154th most ready country in terms of its ability to leverage investments and convert them to adaptation actions worldwide. Iraq is highly vulnerable to climate impacts such as water scarcity, extreme heat and dust storms, which not only strain resources but also intensify and exacerbate existing tensions and conflicts related to governance, resource distribution, social cohesion and migration/displacement. These pressures increase the risk of conflict, especially in already fragile regions where trust between governments and communities is low, intercommunal grievances are deep-rooted, and resources, governance capacity, climate adaptation strategies and conflict resolution mechanisms are lacking.

Content

According to the World Bank, rising temperatures – projected to increase by 1.9-3.2˚C by 2050 – will have severe consequences, including higher heat-related mortality, lower agricultural productivity and more frequent sand and dust storms. The combined effects of drought and desertification are already worsening environmental degradation. In interviews across Iraq, farmers consistently report declining crop yields due to increasing water scarcity and land degradation. These challenges not only threaten livelihoods but also exacerbate tensions over natural resources and contribute to displacement, particularly in areas heavily reliant on agriculture.

Water scarcity is perhaps the most critical issue when examining the interlinkages between climate, peace and security in Iraq. It is driven by a combination of factors, including upstream dam construction, poor water management and outdated infrastructure, climate change and population growth. For instance, water flow in the Euphrates and Tigris rivers has decreased by 30 per cent since 1980, driven by climate change, poor water management, and the absence of binding water-sharing agreements with upstream countries, particularly Turkey and Iran. This trend has fuelled tensions over water access, heightening the risk of conflict between communities, provinces and countries. In interviews with farmers, local authorities and other stakeholders, climate-induced water scarcity was frequently cited as a trigger for disputes. These tensions have been intensified by restricted access to irrigation water and violations of local water-sharing agreements. In addition, the water crisis has profound implications for human security in Iraq, severely affecting agricultural productivity and public health. Contamination of water sources has led to increased social unrest, while flooding exacerbated by climate change is damaging infrastructure, disrupting livelihoods and leading to further displacement (e.g. Basra in 2018, where sewage overflow contaminated drinking water and sparked protests; Erbil in 2021, where flash floods displaced dozens of families). In many cases, these displacement dynamics are worsened by weak governance and a lack of trust in state institutions, which not only hinder effective crisis response but also undermine long-term adaptation efforts at both the local and national levels.

While climate-related risks to peace and security manifest differently in each location, research reveals underlying trends that can be identified in areas where conflict and climate change impacts compound. These trends can enhance understanding of how social, political and economic dynamics shape climate security risks. While there is no simple causal link between climate change and (violent) conflict, it is widely evidenced that climate change affects conflict dynamics and hinders peace.

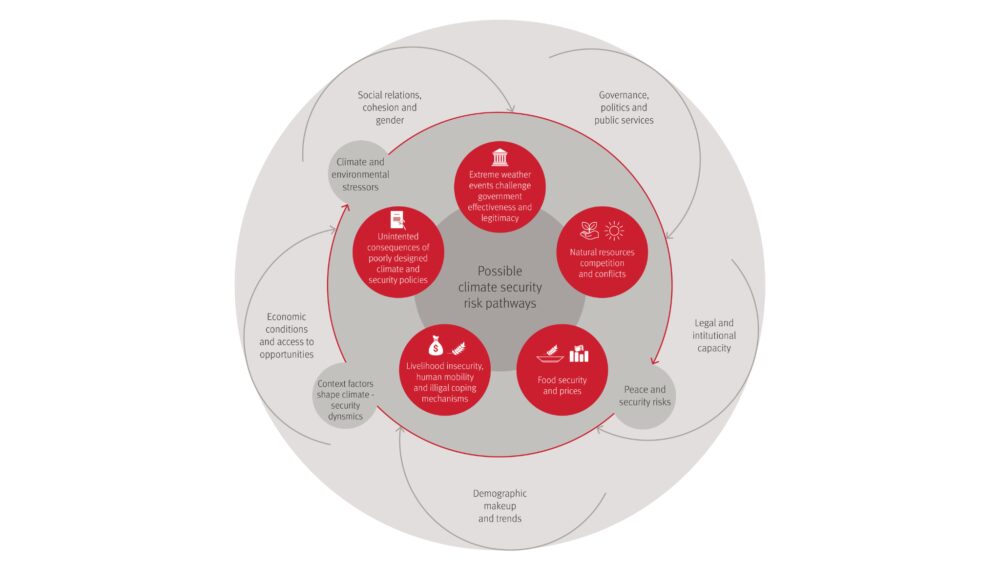

The Weathering Risk (WR) methodology (Learn more) developed by adelphi offers a framework for understanding the interlinkages between climate change, environmental degradation, conflict, peace and security. The framework uses climate security pathways to explore how climate impacts and security risks are interacting. Specific pathways vary by context but are related to natural resources, livelihood and food insecurity, weak governance, climate-induced disasters and unintended policy consequences. Analysing these pathways helps untangle a complex interplay of factors, breaking them down into identifiable dynamics that can be understood and addressed.

We have slightly adapted the WR methodology to fit our purpose in Iraq. These are the key factors we used to assess climate security risks:

- Climate/environmental stressors and exposure (e.g. Which climate stressors are affecting the country? What are projections for the future? Who is exposed when and where?)

- Security dynamics (e.g. What are the main causes and drivers of instability and insecurity? Who are the main actors?)

- Vulnerabilities and resilience (e.g. Is there sufficient capacity to absorb climate stressors? How are different groups affected?)

Based on our understanding of the intersection between these risk dimensions, we mapped out potential pathways to help generate entry points for peacebuilding efforts, ensuring that mediation and dialogue processes address the root causes of conflicts systematically. This approach serves as both a mapping framework and a methodology for identifying and generating entry points for dialogue and mediation, thus ensuring that climate and environmental security are effectively integrated into conflict transformation efforts.

The insights gained from applying the pathways methodology in our engagement can inform the design of future research on the climate-conflict nexus and guide fieldwork on climate security risks with conflict-affected communities. In addition, they can assist in more easily identifying climate security risks and integrating them into mediation and dialogue processes, as shown in Part II. These insights reflect key findings from the initial mapping phase of our engagement, drawing on interviews with Iraqi researchers and partners.

Participant in mapping exercise in Basra, 2022

"Many people came to Al-Zubair from other governorates, and this phenomenon is happening all over Basra governorate. It affected the tribal traditions and customs."

Climate change is significantly impacting Iraq’s social and economic landscape. Agricultural communities in the Dhi Qar and Maysan governorates are experiencing a rise in heatwaves and water shortages. These increasingly frequent events are leading to an increase in crop failures and livestock losses. As a result of these challenges to their livelihoods, many young farmers are abandoning their agricultural activities and migrating to urban centres, primarily Basra, where they have very limited access to basic services or job opportunities and risk being drawn into illicit economies or violence. There is a perception of cultural differences between displaced people from mostly rural areas in Dhi Qar and Maysan and the urban centres of Basra. In addition, the displacement of these populations and the subsequent competition for scarce resources strain local service provision and exacerbate tensions between IDPs and host communities. A government with low levels of trust and inadequate conflict management mechanisms often struggles to find effective solutions to these challenges.

Participant in mapping exercise in Kalar, 2022

“Balajo water channel is located in Kalar district, south of Sulaymaniyah. It is sourced from the Sirwan river. The irrigation channel flows through 23 villages. Some farmers take more water than they’re supposed to, leaving the downstream villages without enough water. As a result, some of us don’t even have drinking water here.”

In the Kalar region, marked by tensions and conflict between communities, several villages are facing a water scarcity crisis. For years, disputes over dwindling water resources have intensified, fuelled by accusations of illegal tapping and violations of water allocation agreements related to the Balajo irrigation channel. These ongoing issues have deepened existing divides and fostered mistrust between the villages. Furthermore, the lack of water has contributed to the displacement of households from some villages.

Participant in mapping exercise in Afak, 2022

“I myself and other women used to craft accessories and sell them at the market. Now, we are unable to sell them because of the high prices of the imported materials we use.”

The impact of climate change is also evident in the reports from many women in Afak and Kalar. They are observing a correlation between drought and a subsequent rise in prices of essential goods, including food and craft materials. This price surge has particularly affected women who depend on selling their hand-crafted goods to generate an income. Due to the increased cost of materials, they are unable to sell their products at the market. In many cases, this significantly impacts their ability to provide a stable and secure environment for their families, including ensuring access to education for their children. The compounding effects of climate change, including extreme fluctuations in food prices and overall food and livelihood insecurity, further exacerbate the existing challenges and security concerns.

Three phases of the mapping process

Design and planning

This section focuses on the initial steps in designing and preparing the interview process, addressing the following key aspects:

- Defining an objective analytical framework and methodology

- Working in a research team

- Formulating interview questions

- Identifying participants

- Choosing a location

Data collection and interviews

This section provides insights on conducting interviews, focusing on practical aspects such as:

- Ensuring the safety of participants and building trust with interviewees

- Actively listening

- Maintaining engagement and reconnecting with participants after the interview

Analysis

This section focuses on the process of analysing interview data in preparation for a dialogue or mediation process:

- Analysing the collected data

- Identifying entry points for dialogue and mediation based on the findings

Phase 1: Design and planning

Defining an objective analytical framework and methodology

The process of identifying climate security risks can be used as a basis for conflict transformation as it enhances our understanding of the climate-conflict nexus in a specific location and provides a foundation for making informed decisions and implementing effective interventions. Before conducting the mapping, it is crucial to define the objective, the analytical framework and the methodology, as this guides the direction and scope of the study. The pathways can be used as an analytical framework to identify areas of inquiry, such as displacement, food security and livelihoods, and ensure comparability between different areas and interventions.

This analytical framework can then guide the development of appropriate interview questions. Interviews help us to generate anecdotal evidence from people rather than producing quantitative data. By focusing on people telling their stories, this qualitative approach offers narratives and insights into how climate and environmental changes affect conflict dynamics and human security. In turn, these narratives provide a basis for dialogue and mediation efforts. As this methodology does not yield quantitative data, it is important to verify and validate findings within qualitative approaches. This can be achieved through additional consultation meetings with various stakeholders, such as technical experts, local authorities and tribal or religious leaders.

It is also important to work with climate data, bring context and climate expertise into the team, where possible, or collaborate with partners who have access to and can interpret such data. To ensure the robustness of our work on climate and environmental issues, the integration of climate data alongside qualitative insights will help to provide a more comprehensive understanding and strengthen the validity of our findings. The combination of both data types will enhance the overall soundness of our analysis and produce the most accurate picture of the context possible.

For example, when asked about water accessibility, interviewees reported that they now have to dig wells down to six metres instead of three. While verifying these exact figures may be challenging, the crucial takeaway is understanding the lived experiences of the interviewees. At a later stage, it will be important to verify the figures with local authorities and experts and check them against available statistics. However, for research purposes, the key message is the increased difficulty faced by the interviewees, which must be placed within the broader context of climate change-induced livelihood impacts, potential tensions and conflicts.

Working in a research team

A research team can consist of an interviewer, a note-taker, a data analyst and an expert with local networks to identify suitable interviewees or secure access to the area. Interviewees can be included as active subjects, providing feedback on the questions and setup. For example, technical terms relating to climate change can be difficult to understand, and distinctions between climate change impacts and environmental stressors may not be widely understood. Clarifying these concepts based on feedback from interviewees ensures that the mapping accurately captures their perspectives and experiences.

A team-based approach to the mapping enables a broader range of issues to be explored during the interviews. For instance, one team member can observe the interviewees’ body language, which may provide insights that inform the outcomes. These observations may also indicate whether changes in security arrangements or other adjustments are necessary. Additionally, in certain areas, it may not be customary for a male interviewer to hold one-to-one discussions with women. In such cases, the presence of a second person in the room can help to alleviate potential concerns.

Formulating interview questions

Once participants have been identified, it is essential to develop interview questions that are based on and tailored to their individual experience. It is crucial that the research team respects the interviewees and meets them on an equal footing. This involves framing questions in a way which allows interviewees to share their perspectives effectively. Urban residents may connect better with topics such as lack of services, while farmers can offer insights into agricultural adaptation needs. A recognition that perceptions of conflict levels vary is also important. Some interviewees may deny that conflicts or climate-related stressors exist as management strategies are in place. Scenario-based questions may be helpful in addressing feelings of unease that may arise when discussing conflicts; they may also be useful for evaluating and assessing conflict resolution mechanisms and climate change adaptation strategies.

For instance, researchers reported that people were at times not very vocal when asked directly about conflicts over water scarcity. Yet when researchers asked about their reaction to reduced water supply, they explained and elaborated on certain dynamics and coping strategies, such as recourse to authorities, legal action, protests, livelihood adaptation or migration to other areas. This approach aims to provide an understanding of people’s situations without judgement or discomfort for respondents. Since climate change experiences vary widely, starting with a brief introduction or a video on climate change and environmental stressors can establish common ground and initiate a conversation, especially at the beginning of focus group discussions.

For example, if you ask ‘Do you have a conflict?’, people might just respond with no. Instead, use scenario-based questions to explore the situation. For instance, you could ask ‘If allocation of water shares in your area were reduced from once a month to once every two months, how would you respond?’

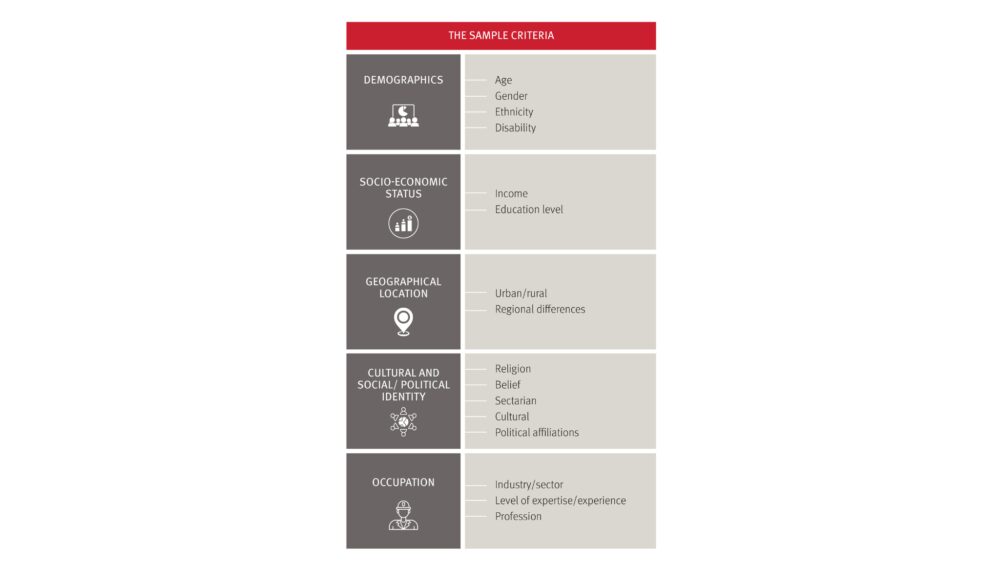

Identifying participants

The impacts of climate change and conflict are felt by individuals in diverse ways. A combination of focus group discussions and key informant interviews offers scope to explore different narratives. Key informant interviews with representatives of local authorities or technical experts can delve into specifics such as climate change adaptation plans and measures.

In parallel, focus group discussions with community members facilitate the process of gathering data on perceptions of these plans and their implementation. By engaging an inclusive group and adopting an intersectional perspective, particularly for focus group discussions, a more holistic understanding can be gained. Predefined criteria are helpful in identifying participants inclusively; this requires a thorough understanding of the context to ensure that various vulnerabilities are considered. At times, it may be necessary to hold separate focus groups, for example with young people and women, as some participants may feel more comfortable speaking in settings where they are among peers.

Choosing a location

The purpose of an interview is to connect with individuals who share their stories. The setting and scope of an interview are often influenced by local conditions and norms. There is no one-size-fits-all approach, and it is crucial that interviewees feel comfortable sharing insights into their circumstances and experiences. It is helpful to explore different interview formats in order to encourage more openness.

For instance, an interview might take place at the interviewee’s official workplace – e.g. in their office – and focus on matters related to their role. It could also involve interviewing a farmer on their land, allowing them to show how climate change has directly impacted the land and explain how this affects their livelihood and security. While in-person interviews are often perceived as more direct and can help in creating an atmosphere of trust, one possible advantage of online interviews is that the interviewee can choose a location of their preference where they feel sufficiently at ease to share their experiences. Alternatively, the interview could be conducted online with the interviewee sitting in their garden, allowing them to feel connected to their surroundings and at ease while sharing their story.

Checklist: Sending invitations to participants, booking suitable rooms for the focus group discussions, organising transport for the research team and participants, providing coffee, tea and refreshments, depending on the length of the interviews.

One interview with a tribal chief took place online, with both the chief and the interviewer sitting in their gardens. This informal setting helped to create a relaxed mood that was conducive to their conversation, which lasted 2.5 hours. In contrast, another interview with a different chief from the same region was conducted in a restaurant and lasted only 35 minutes. The restaurant setting made it more challenging to focus and engage deeply with the stories and questions.

Phase 2: Data collection and interviews

Ensuring the safety of participants and building trust with interviewees

Introducing the team, the interests and purpose of the exercise and what happens with the data, thereby being transparent, can help build trust and establish the basis for effective communication, especially in sensitive conflict environments. In contexts where political affiliations or socio-cultural dynamics are significant, the research team should be sensitive towards the interviewee and, from the start, use appropriate language, avoiding terms or topics that could cause discomfort or tensions. The team should be aware that the interview guidelines provide a structure but remain a flexible tool, with scope for adaptation to each participant’s time constraints and priorities.

It is important to explain the purpose of the mapping and the context in which it is conducted. At the start of interviews, the goals, such as learning about social, economic, political and environmental issues, including climate change, in the communities concerned should be clarified. At this stage, even if the mapping is intended to promote further dialogue or mediation initiatives, the primary task is to listen to the interviewees. Although it is hoped that the findings will inform decision-makers or other organisations and encourage them to provide support or aid in response to conflicts or specific needs, it is important to explain the purpose as well as the limitations of the mapping transparently. This is particularly relevant for communities heavily impacted by shrinking livelihoods or forced displacement due to climate change. Since the mapping itself cannot promise positive changes to the challenging conditions faced by these communities, communicating this from the outset is crucial.

In our interviews, we frequently hear allusions to entities that interviewees hesitate to name directly, often because these are influential or conflict-related actors. Sometimes, these groups are involved in providing services, and interviewees might refer to them in subtle or indirect ways. Given the significant impact these groups can have, it's crucial for interviewers to handle these topics with great sensitivity.

With regard to safety, it is essential that participants only contribute if they feel comfortable and safe to do so and all information provided will be treated confidentially. Particularly for sensitive contexts, participants should be reassured at the outset that they may omit questions they do not wish to answer and that they may end the interview at any point in time. While climate change is generally perceived as a less sensitive topic in the field of conflict research, some questions might lead participants to express dissatisfaction or criticism of authorities, potentially putting them at risk. In some contexts, authorities may also be suspicious of individuals participating in interviews, making it essential to take precautions tailored to the specific setting. Above all, safety must remain the guiding principle. Interviewers should therefore approach every interaction respectfully and ensure that all contributions are treated sensitively to avoid putting participants at risk.

Active listening

When conducting interviews, it is essential to remember that the interview guidelines serve as a flexible tool rather than a rigid script. As some participants may have limited time or insights on certain aspects, certain questions may be omitted. The focus should be on active listening and allowing all participants the opportunity to share their experiences and perspectives. Ensuring that each person has a chance to speak in focus group discussions also fosters a more inclusive and comprehensive understanding of their viewpoints.

Maintaining engagement and reconnecting after the interview

To ensure comprehensive and accurate data collection, researchers may need to visit participants again or gather additional information to address gaps, clarify responses or explore new insights. This iterative process is crucial in complex and evolving contexts, as it helps validate findings, enrich data quality and capture all relevant themes. Re-engaging participants also builds trust and reinforces their role in the mapping, enhancing the overall reliability and depth of the study. Equally important is informing participants about how their responses and data will be used and committing to share the outcomes of the mapping or provide follow-up information. This approach can help reduce research fatigue, especially in contexts where individuals are frequently asked to participate in similar processes.

Phase 3: Analysis

Analysing the information

The pathways can be used as a guiding analytical framework to categorise outcomes based on their relevance to factors such as livelihoods, displacement/migration and food (in)security. If the mapping was conducted in multiple locations, this approach also facilitates comparison of these locations based on their vulnerabilities and/or mechanisms for adaptation to climate change impacts or conflicts related to environmental degradation. For example, a report can be structured to highlight commonalities and differences, analysing the main contributors to these patterns. Subsequently, the report can delve into each location in more detail, providing specific insights and data.

Generating entry points for dialogue and mediation

Before selecting an entry point, it is essential to first identify potential entry points for dialogue and mediation processes by breaking down complex climate security dynamics into components. Climate security pathways serve this purpose by mapping out how climate impacts interact with existing social, economic or political tensions. This structured analysis helps uncover specific points where constructive action – such as dialogue or mediation – can help to ease tensions and find solutions. Entry points may emerge at different levels and – once these entry points are identified and understood – they can be effectively assessed and weighed for the engagement.

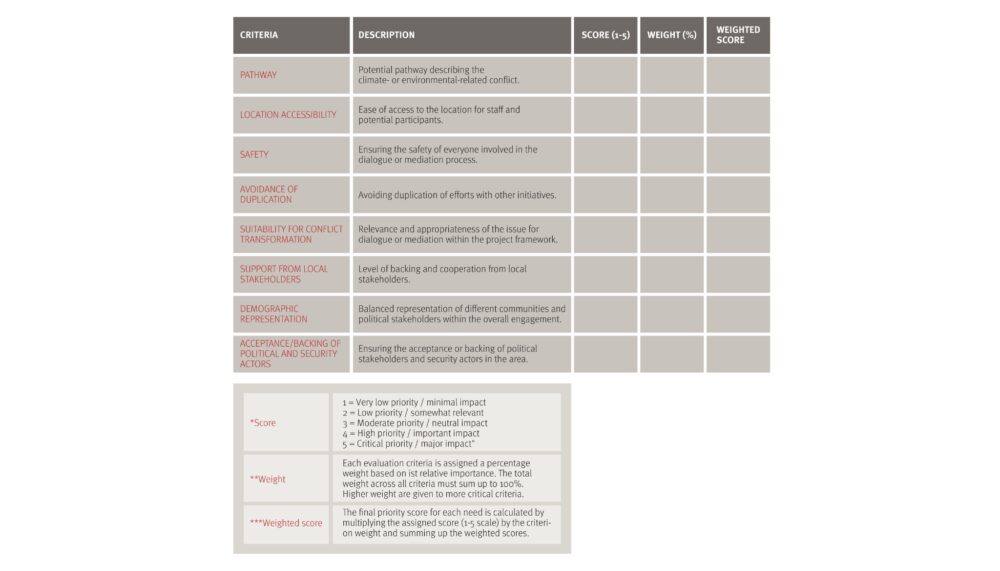

Following this, a matrix can systematically prioritise entry points for dialogue or mediation as a basis for informed decision-making. Within this matrix, predefined characteristics such as identified potential pathways, location accessibility, safety of staff and participants, avoiding duplication of other efforts, suitability of the issue for dialogue or mediation, support from local stakeholders, balanced demographic representation of different communities and political groups, and acceptance from political stakeholders and security actors can be employed. A scoring system can then be applied to select specific locations for engagement based on a structured assessment of various factors.

Within the context of climate-conflict assessments, it is important to bear in mind that conflicts relating to resource scarcity may escalate differently in summer due to factors such as drought, heatwaves and scarce rainfall compared to winter. A matrix assists in capturing these seasonal variations that impact the dynamics and severity of conflict. It also facilitates the identification of necessary preparatory steps. Allocating sufficient time to transform identified climate security pathways into entry points for dialogue or mediation is crucial. This may include allocating further resources for additional consultations and verification meetings.

Continue reading

Now you know the tools to analyse climate-related conflict risks. Next, learn in Part II how to implement climate-focused dialogue and mediation approaches.

Part II (Implementation) Back to the main page

Get in contact

What do you think about the toolkit and how do you plan to implement it within your project?

We would like to hear from you. Please, contact us via email.

Thanks for your interest

If you find this publication useful, please consider making a small donation. Your support enables us to keep publishing.